Kevin Coval Talks About Everything Must Go, Wicker Park in the '90s and More

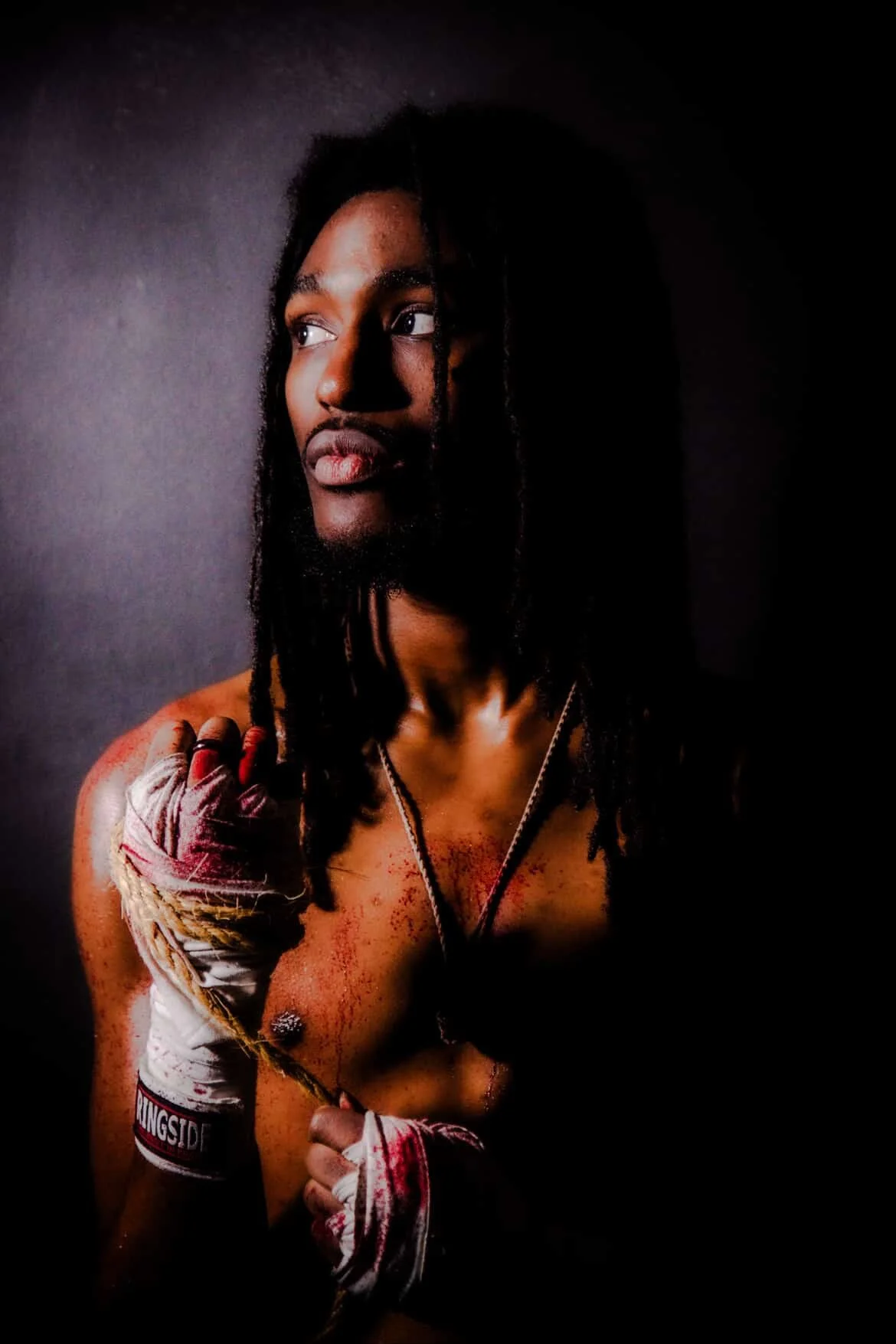

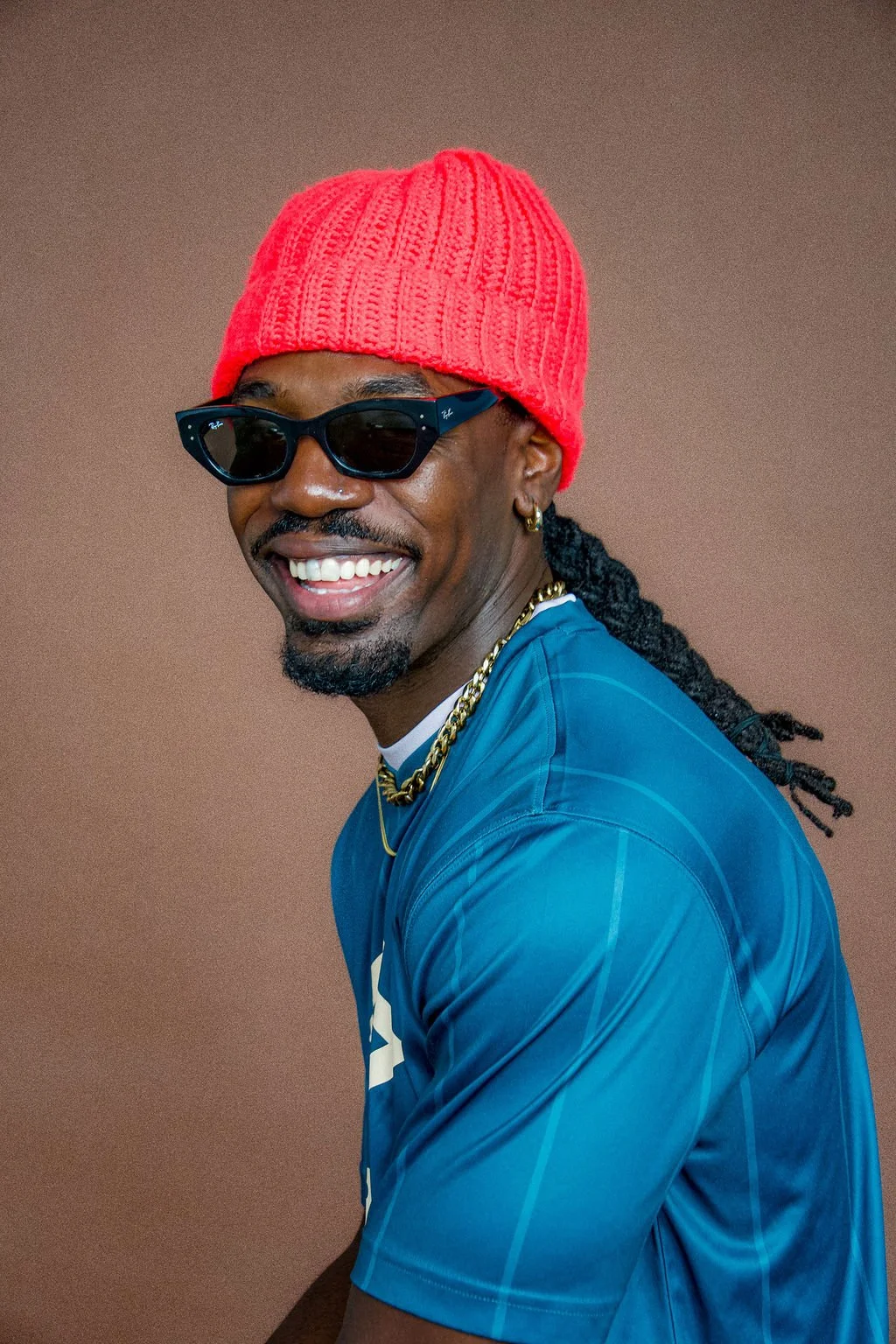

Photography by Michael Salisbury

There's tons of work linked to the name Kevin Coval; Founder of Louder Than a Bomb, Artistic Director at Young Chicago Authors, and podcast co-host of The Cornerstore show. And that's just to name a few. There's also his sartorial choice: the snapbacks —which I'm sure are his most recognizable garment. However, above it all, he was first a poet who sharpened his literary sword in the burgeoning Wicker Park neighborhood of the '90s.

Since then he has published seven books. His last one, 2017's A People's History of Chicago, was a collection of poems recounting the stories of marginalized people who shaped and had a profound impact on the city. While writing it, Coval's editor Nate Marshall noticed a recurring theme of gentrification but also two big thematic ideas explored within the text. Heeding Marshal's advice, Coval separated the motifs into two different books.

Everything Must Go is the second book that spawned from those sessions and is set to drop on October 1st. Here, Coval switches it up and shares from his own lived experience what it was like to reside in Wicker Park in the 1990s as a young artist. He uses this book to recount his adventures, misfortunes, and his experience watching gentrification stomp its footprint on the umpteenth Chicago neighborhood.

As part of his promotional run for the book, Coval met with the These Days team at South Facing Windows studio. After the usual small talk introductions, Kevin was pleasantly surprised to see me. As a former student at YCA's Chicago Beat and an intern on The Cornerstore, I'm sure it threw Kevin off guard to see that the roles had slightly switched. From helping him conduct interviews to providing him with questions, our conversation had a fun dynamic.

Once we settled in, Coval went in-depth about creating this book, his old stomping grounds, and his reckoning as a white person existing in a neighborhood of mostly people of color. Read a slightly edited and condensed version below.

Can you give us a little background and brief synopsis on the book?

It's pretty much about Wicker Park in the '90s when I first fell into the neighborhood, lived there, and see it go through a series of pretty dramatic changes. My grandfather came from the Ukraine to that neighborhood at the turn of the 20th century, and I came into the neighborhood at the end of the 20th century. It's specifically about that neighborhood, but it's wrestling with things that a lot of cities in America and beyond are also dealing with. What does it mean to develop neighborhoods and what happens to the people who have been there? The book to me is kind of an ode to the people and the places that were there that had such an impact on me as a young person, as an artist, and some of the artistic communities I was a part of.

When you first moved there, how old were you?

When I moved there, I was probably 20.

How was that, being a 20 year old in Wicker?

It was exciting. In some ways, I think this is a book about me maturing —I hope. It's focused on that time of my life where I was a knucklehead, and matured and got a little more measured to my approach to life. That neighborhood and the people in it helped raise me. I was lucky to fall into such a vibrant artistic community that also looked out and cared for me in a way when I was a younger writer and a younger artist.

How was that like financially? If I were to move to Wicker in my 20's I would have to have three other people, maybe four, just to afford a bedroom in a Wicker Park apartment.

Well, it was a lot cheaper then. [In the boo] I talk about the roommates that I had. We moved into a three-bedroom apartment. Three of us. All of us had a few jobs. I think that a part of what Wicker allowed at that moment was an opportunity for young people and young artists to afford a life in the arts. All of us had side-hustles, I didn't know anyone who was full-time off of art. That wasn't even in the realm of possibility. That was beyond a dream at that point. The dream was to have a side hustle and also be able to make a life that you could create in. Everyone I knew had a side of gigs; legal and illegal. It was people who worked, people who hustled. A lot of Latinx families who worked, then a lot of Polish and Ukranian folks and this community of a lot of weird artists. A kind of bohemia in some ways. It was possible to live that life.

I know a totally different Wicker now. Hella bars, hella restaurants. It's kind of "hipsterish" but it's still for a certain type of people.

I don't even know if "hipster" was the term in my era. I think the thing that we begin to see is the encroachment of what we called "yuppies." You know, young urban professionals who eventually kind of erased what was once a working-class neighborhood into essentially what you see now. The book is also about seeing those clues. In hindsight, I could read it as the beginning of the end of what that neighborhood was.

What do you think was your first inkling of "shit's about to change?" A lot of people joke "you know if you come into a certain neighborhood, and you see they moved a Starbucks, it's about to get real."

They closed a spot that was a real gathering space —a coffee shop called Urbis Orbis, which I write about in the book. [It was] one of the first places where I met what would become my friends. I would imagine it was that for a lot of people. It seemed to be a place you could sit all day for just to chill and read. There were people playing chest and maybe there was music on. People were thoughtful and comfortable in that space, sometimes to the degree where they were obnoxious. There were a lot of philosophy heads, but also a lot of sculptors and painters and drug dealers. Once that closed, it became a gym afterward. The Real World, the MTV show, set up shop in 2001 in that same building. So to me, the book is marking a time period between about '94 to 2001. There are people who lived there before I did, who would say the death was much earlier than that. But I use that as a demarcation as to when it really began to be over.

How is this book different from your other books?

I started to write [Everything Must Go] while I was writing A People's History of Chicago. Nate Marshall was one of my main editors and noticed that I was starting to write two different books. I was so far in the idea of People's History that Nate wanted to tackle that first and then have this gentrification/Wicker Park book be something else.

How did the collaboration with Langston come about?

I met Langston at a Gallery show he put on in Humboldt Park on Kedzie and North Ave. When I walked into —basically what was a storefront that Langston transformed into a cartoon—he had illustrated the walls. I was already starting to write this book, knowing that I wanted it inspired by graphic novels. I try not to let synchronicity go by me, if I meet someone and I'm thinking about something, I'll just be like "yo! we should do this!" I love collaborating and inspired by collaborators. I met Langston, I fell in love with his work and, soon after that night, talked to him about this idea, and he said he was down.

What is he providing?

He illustrated the whole thing. Some of the poems are treated as a graphic novel where the text is in the margins, and the illustration is at the center. For most of the poems, he has illustrated around the poem to punctuate what's happening in the text. He influenced me in writing too. As I would start to get him early work, you would ask questions about the work that made me think or remember stories that I wanted to tell. So I think we work well back-and-forth, bouncing ideas off one another.

Did you have difficult memories you went back to?

Oh yeah. I was young and making bad decisions. I was naive and running around with folks that I wouldn't run around with now. I felt I had to perform a certain kind of masculinity that I don't feel the pressure of having to perform anymore. Also, just wasn't established in any sense of the word. Everything was very tenuous. Life is tenuous, but when I was young and in situations where I was job to job, tip-to-tip I drove a truck at that time, I worked at a restaurant at that time, involved in various illicit activities at that time and shit was tenous.

Did you have a poem that was really hard to write down on paper?

There's a poem in there called "Girl From The Neighborhood." It's kind of a funny, but also embarrassing and heartbreaking story about me dating a girl from the neighborhood. I was hesitant to write it because it's about being clowned and played. In the book, I'm also trying to take responsibility for some of my shit. I'm also a white person moving into a neighborhood that's not white majority. There's a poem called "White On The Block" that's about the first night I moved into the neighborhood and met some of the folks and street organizations outside. How my ability to walk in the neighborhood is so different from their ability to walk in the neighborhood. Also being cognizant and aware and wrestle with that means.

From the outside looking in, anybody can say "oh this white guy who does this and that…he's occupying this space." How do you try to not take up a lot of space in these communities?

I think I benefited from a very thorough education in the cipher and open mic. You got your turn, but for the most part, you would be quiet, and you would listen to other people. To me, that's also probably a good metaphor when we think about democracy. You are your unique self and also intimately connected interwoven in the whole. Your unique self should not overshadow the whole. It means you get to be you. Now if you say wild shit, you will also be dealt with, and I learned that too. I think those are valuable lessons as a young white cis-head male to learn. I should be called out if I say some reckless shit and I was. And I think that's beneficial in my own maturation as an artist and as a dude.